Every week, Zikoko asks anonymous people to give us a window into their relationship with the Naira. Some will be struggle-ish, others will be bougie–but all the time, it’ll be revealing.

The subject of this week’s story just hit 18. He’s also at his first 9-5 ever, as an intern. When he’s not in Nigeria as an intern or on holiday, he’s a student in the UK.

When was the first time that you wanted money and your parents were like, what for?

I think it was that time I wanted money for a website I was working on – I’d already spent £350. I spoke to a company that was supposed to do it, and they quoted $5000.

Then my parents asked, “How do you intend to get the money back? Have you thought about it? What sources of revenue will bring it back?” I couldn’t figure this out.

It made me start asking myself what the point of making something people could use, but still not have a way to sustain it.

Especially since it was something that would have running costs after.

Did you get the money eventually?

No. That was the end of the website. It’s interesting, school always encourages you to feel like you can do anything you want – and it’s true. But there’s a balance of opportunity cost. You can do this, but are you going to have the time? Are you going to be able to look at it properly? And most importantly, are you going to get it back?

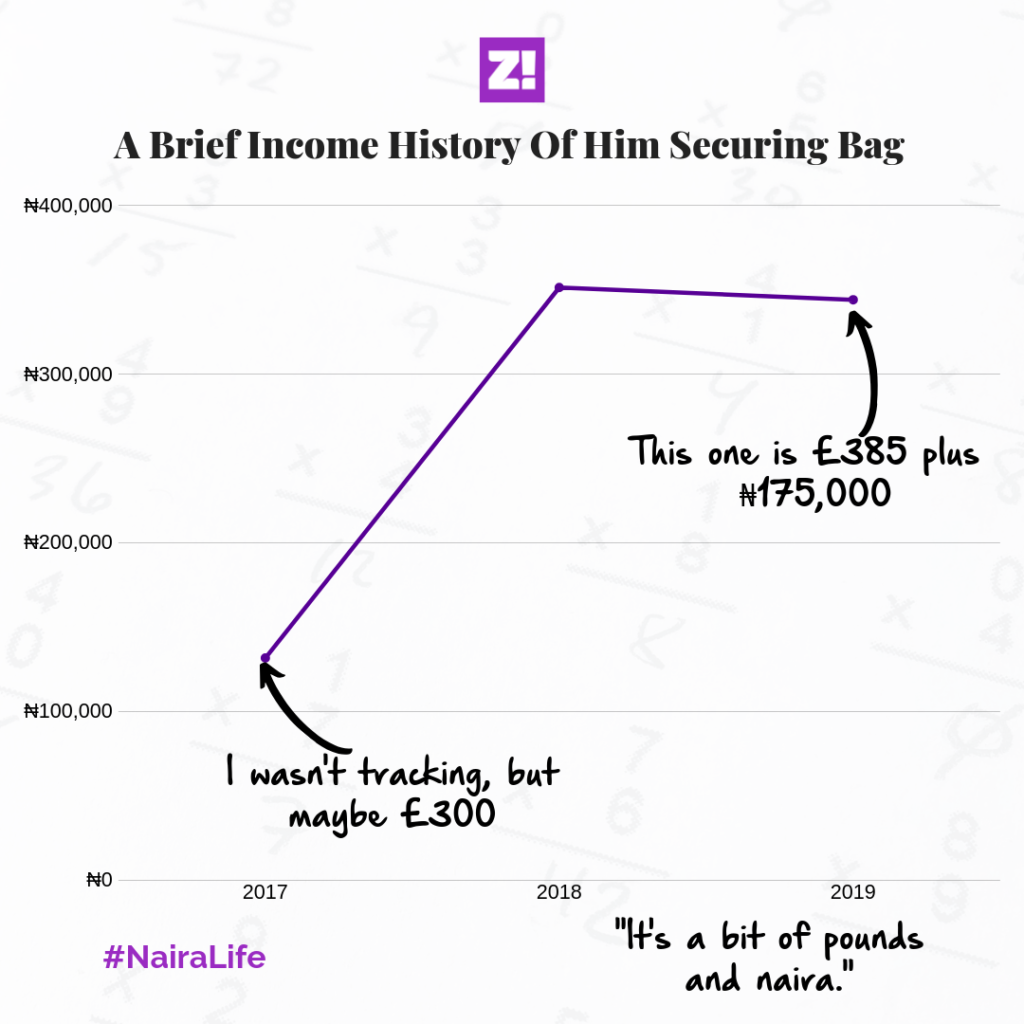

That’s when I started tracking how much I made from commissions, how much I spent on equipment, and on financing the projects I was working on.

How old were you when you asked for the money?

16. I’d had other expenses before. Like there was this app that I needed to pay 100 dollars to keep on the app store. And they paid for that.

What are the things you do that fetch you money?

Graphic design and photography. I started designing when I was 14 – self-taught. Then album covers for friends in 2015. I charged like ₦5000 for each –

– Mad thing, but you just mentioned the naira for the first time.

Hahaha.

Okay, back to the things that fetch you money.

I didn’t earn a lot, because Nigerians didn’t see the value in it at the time. The question is, was I not finding the people who were willing to pay? Was I not good enough at the time? Or were people not just ready to give money to a 16-year-old?

Anyway, by the end of 2017, I was charging £100 per logo and £30 for posters.

What are some interesting things you’ve heard about money from your friends?

A couple of things. I’ve heard someone say she has to marry a rich husband. I think that was half a joke though. Hopefully. Then there are the ones that say, “It doesn’t really matter for now, my parents can cover stuff. Why am I bothered?”

Why now though?

I feel like I have a privilege I want to take advantage of. I don’t need to pay rent and I still get financial support from my parents, big time. At this point, I’m still making massive loss in a sense, because my expenses are way more than I’m making on my own.

I still have that advantage for the next two or three years. The way I see it, I’m making a time investment now, buying equipment now that I can, and setting things up properly. By the time I’m no longer under my parents’ care, the investments I’m making now, would make it easier for me.

If you come out of uni and you don’t have a job or means of income, it puts you at a disadvantage, because now you’re thinking about taking your life into your own hands. I feel like that’s what puts a lot of people into system jobs – it’s not really what you want to do, but it’s what’s available to you.

I want to avoid that period where I’m like, what the hell do I do?

That makes sense.

Truth is, there are friends in my circle that will probably get big ass grants from their parents as soon as they finish school. I might get that too, but the way my parents are, it’s not going to be something I’ll get easily. Also, there’s that part where I just want to make something of myself. My grandparents weren’t rich – in fact, they were on the verge of being poor. But my parents managed to make something of themselves. So I’m like, why do I have to wait for my parents when I can just improve on what they’ve already started?

That’s an interesting way to look at it.

I also think generational wealth can be a massive ego dump on kids. It can make kids feel like they’re better than other people. It’s one thing to be better off than other people, it’s another thing to think you’re better. It can be dangerous when you start to feel like the latter.

Okay, let’s talk about your monthly income.

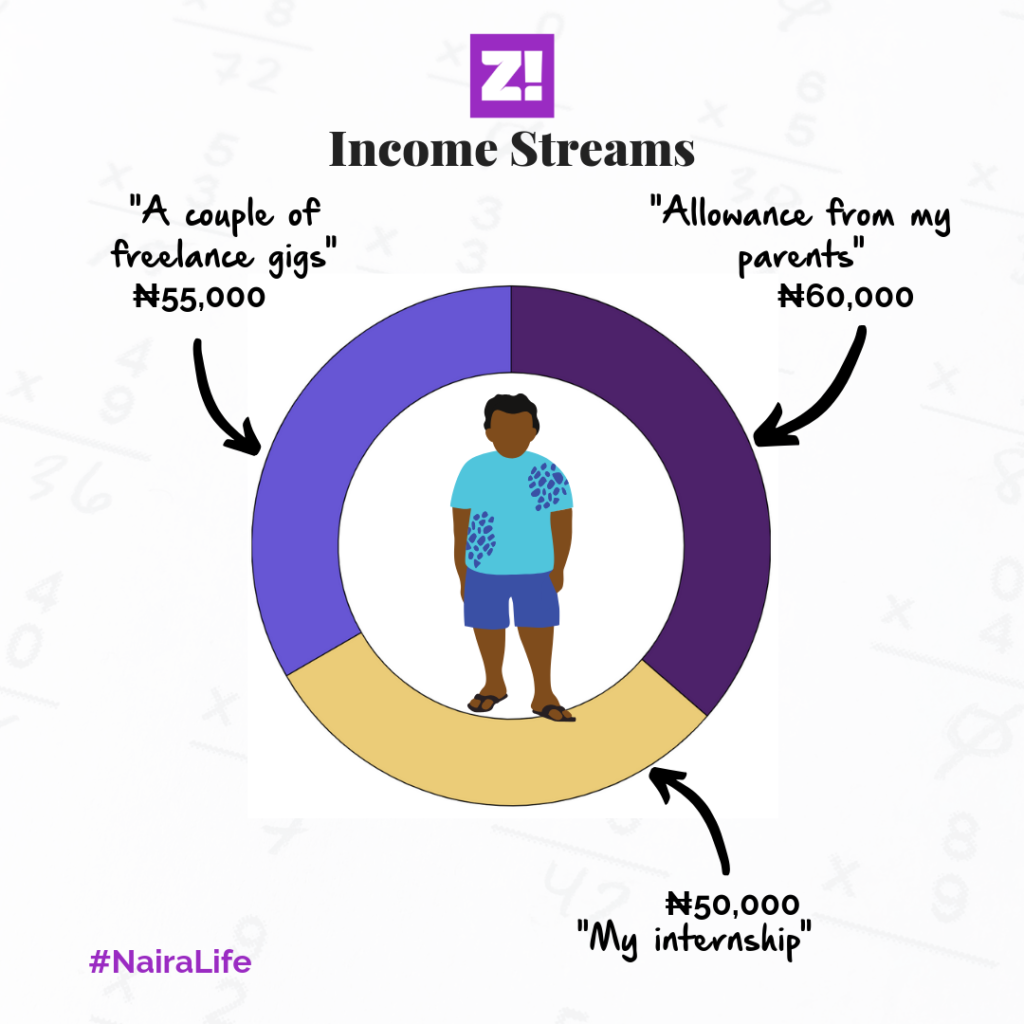

I only just started getting a set monthly income – I’m currently in my first 9-5 as an intern.

People tend to have fixed expenses. But for me, my allowance from my parents is mostly meant to be lunch money. So, food is 60k. Then I spend 10k per week on cabs. I use cabs when my folks’ car is unavailable – that sounds bougie AF. Then I have a bunch of subscriptions: about 24k in total.

Do you feel like you should be earning more money?

Yes! I undercharge big time. One thing you can’t change is perception. If I was 25, doing the things I’m doing now, I’ll probably be able to charge a thousand pounds for a logo. When you’re working with a 25-year-old, you know they have bills to pay, and you won’t want to do them a disservice. Also, I don’t have that much work experience, so people don’t trust me very much even after seeing my portfolio. It’s like people aren’t sure if it’s a fluke or a valid representation of skillset.

If I was producing this type of work at 25, I’d be earning way more.

How much do you imagine you’d earn if you were 25 today?

That’s a good question. I’ve never thought about that. Assuming I stop working 9-5, and some things I’m trying to put it in place is set up the way I want them to be, I’ll be able to make about £3000 a month. I dunno if I’ll be working in Nigeria, but if I work here, probably a mill a month. Now that I’ve said this, I would probably have to check back when I’m 25 to see if I was just chatting kid shit or not.

How much do you think it would cost to fund age 25?

Like, if I had to pay for everything myself? Per month…? Wait. How much is rent?

Let’s start with where you live, how much do you think it costs?

I have no fucking clue. How much is rent? Wow, there’s so much you have to think about when you’re old. Filling your car up with petrol. Electricity bills. Food. Faaji. I don’t know how much that costs! I can’t even start to think about it.

You see, this is one of my fears because the money I’m making now doesn’t mean much. Someone actually working might spend it on petrol in a month.

By the “money I’m making,” are you talking about the 165k?

Okay… This is so confusing because I know that the average earning for an entry-level person in Nigeria is between ₦50k and ₦200k per month. This has me fucked up because I feel like rent for a house where I live will be more than that. Unless I’m delusional. How much does a bank teller earn?

About 50 to ₦80k.

Yeah! That’s actually what I’m actually referring to. I’m so confused as to how someone would earn ₦30k from a full-time job and not be dead.

That’s minimum wage, and I know a couple of people who earn less.

How does a person even survive? Where would you live in Lagos? You can barely live on a bank teller’s wage in Lagos. How would you do this on a minimum wage…? That’s quite scary! How do you hack this?

What do you think?

You can squat…?

That’s the thing – growing up the way I did, you don’t get a full insight into the way Nigeria really is. It’s almost unfair to us, because without understanding exactly what’s going on around you, how do you even begin to help? A lot of people my age say that Lagos is actually a great place.

In your circle

But there are people living in a manner that seems impossible on paper. When we don’t see that, you start to ask, who’s done us the injustice; is it our parents? Probably. Because when you don’t see that, how are you supposed to even appreciate what you have? How do you even begin to think of how to help the country as a whole or the people on the other end of that shit?

Going to work every day made me realise that low-income earners are packed into some areas, and no one cares about them. I saw people bathing outside, not because they chose it, but because the communal shower space is open, visible from the street. It’s like slum living.

It is slum living.

Everyone has privileges, but when did you first realise yours?

Between the time I was 8 and 10, and probably from a couple of places. My parents had people working in the house, and I think from that point, I noticed some differences. We’d travel, but the domestic workers didn’t. I wouldn’t say that’s when it became apparent. At that time, it was just like, that’s life.

But then, the true realisation came in this period of my life. It was last year I started to realise that one of the reasons Nigeria is the way it is, is because a lot of the things we use are imported ideas. Remnants of colonisation. If you ask me, the reason Nigeria looked and felt better just after white people left is that the information was just passed down.

After that – and this is theory – more and more people started migrating to cities. When people come from less developed places, they pick up what’s left of what was taught. Enforcement isn’t as strict, and people start to get away with more and more, the level of how well stuff works just degrades. And more people come in and pick up the remnants and bad habits.

Another thing as well is, we’re not very innovative. We haven’t thought for ourselves how to make stuff work for us. And the only way these people can learn how stuff should even begin to work properly is from exposure. And you can only really gain exposure by going to places where things work the way they’re supposed to.

My new point of realisation was that, not only are people not financially empowered, they are also – for lack of a better word – not mentally empowered. Because there really isn’t much thinking going on.

How are you supposed to think about what you can’t conceive? What does a person working in the market think about on a day to day basis? It’s hard to think about much when you’re in hardship, because all you can think about is, “Where is my next meal coming from? How much have I made today?”

Coming to the point where I realised that thinking about innovation is not evenly spread among Nigerians is the point where I realised my privilege properly.

Okay, okay. Let’s talk about other stuff. What’s something you really want but you can’t afford?

A car. I actually really want a car. I’m currently borrowing my mum’s car, but I want to borrow as little as possible. I want everything to be clear, like “this is my own person as an adult.”

You’re in a hurry to adult.

That’s what my parents say. There’s the thing about ‘waiting to be matured’ that people say. I don’t get it. It’s not as if we’re getting stupider as a species. Why do I have to be babied? I don’t believe you can truly accept responsibility until you’re given responsibility. Raising kids without giving them responsibilities is kind of dumbing them down.

What are old people’s assumptions about 18-year-olds and money that piss you off?

Because I spend a lot, people assume that I’m not saving for the future or something. I’m not stashing money now so I can get things that’ll help me stash money later. Another fucking assumption is that I dunno how much it means to be an adult. Because… apart from rent and shit… Wait.

Hahahaha.

Okay in retrospect, it’s actually true. I dunno. But a lot of people feel all the money I get goes to enjoyment.

Let’s talk about enjoyment. What’s a good day out?

Probably spending 10 to 15k on one meal. Fuckkk. That’s my guilty pleasure. Not much else. I don’t actually spend much on wayward enjoyment.

Financial happiness. On a scale of 1-10.

Right now? I’m very fucking happy. I think I’ve finally reached a point I wanted to get to. At this point, I can say that if my allowance was taken out, I won’t be affected. I’ll still be able to run as my own person.

The constant struggle to be your own person.

Pretty much.

What’s something you wanted me to ask that I didn’t ask?

The only thing missing is how much my parents spend on me, which I honestly dunno. Like, kids are just one big ass investment. But it’s probably pushing £50k a year.

How much of a chunk do you think that takes out of their finances?

I wouldn’t even know to be honest.

Oh wait, I just checked the listing of the house when they bought it.

How much did it cost them?

₦150 million.

This story was edited for clarity.

Check back every Monday at 9 am (WAT) for a peek into the Naira Life of everyday people.

But, if you want to get the next story before everyone else, with extra sauce and ‘deleted scenes’, subscribe below. It only takes a minute.

Every story in this series can be found here.