In Nigeria, the nation’s land force arm of the Nigerian Armed Forces is known as the Nigerian Army. Since its inception in 1863, it has been known for both challenges and achievements—from successful terrorist raids to the most inhumane human rights abuses.

Soldiers gesture while standing on guard during Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari’s visit to the Maimalari Barracks in Maiduguri on June 17, 2021. Photo by Audu Marte/AFP via Getty Images

Recommended: Bad Since 1999: The Nigerian Army Needs Reform From Wickedness

But how did they get here? What’s the Nigerian Army origin story? How have they evolved time?

To answer these questions, we need to take you all the way back to 1862.

The Pre-Colonial Era

“Glover’s Hausas” And the Rise of Constabularies

The first mention of an armed force in Nigeria dates back to June 1, 1863.

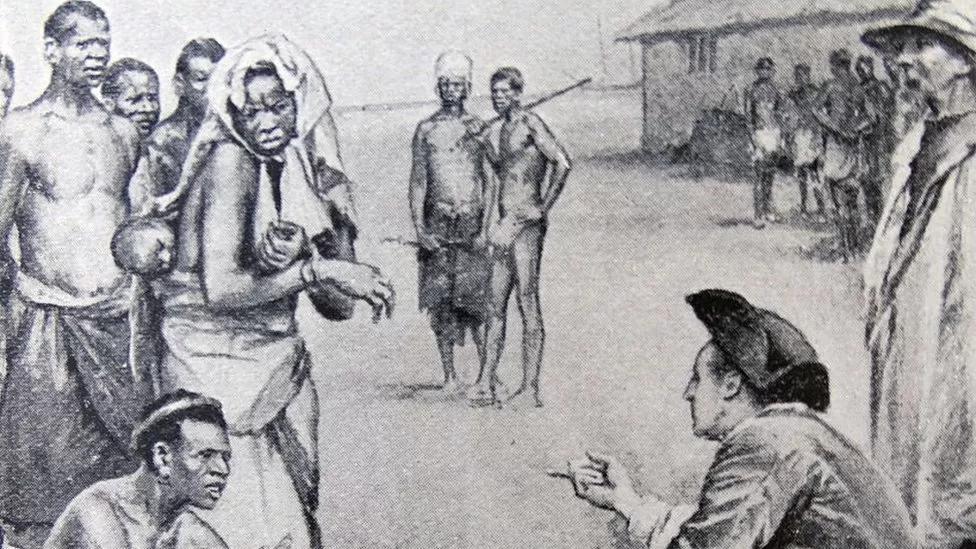

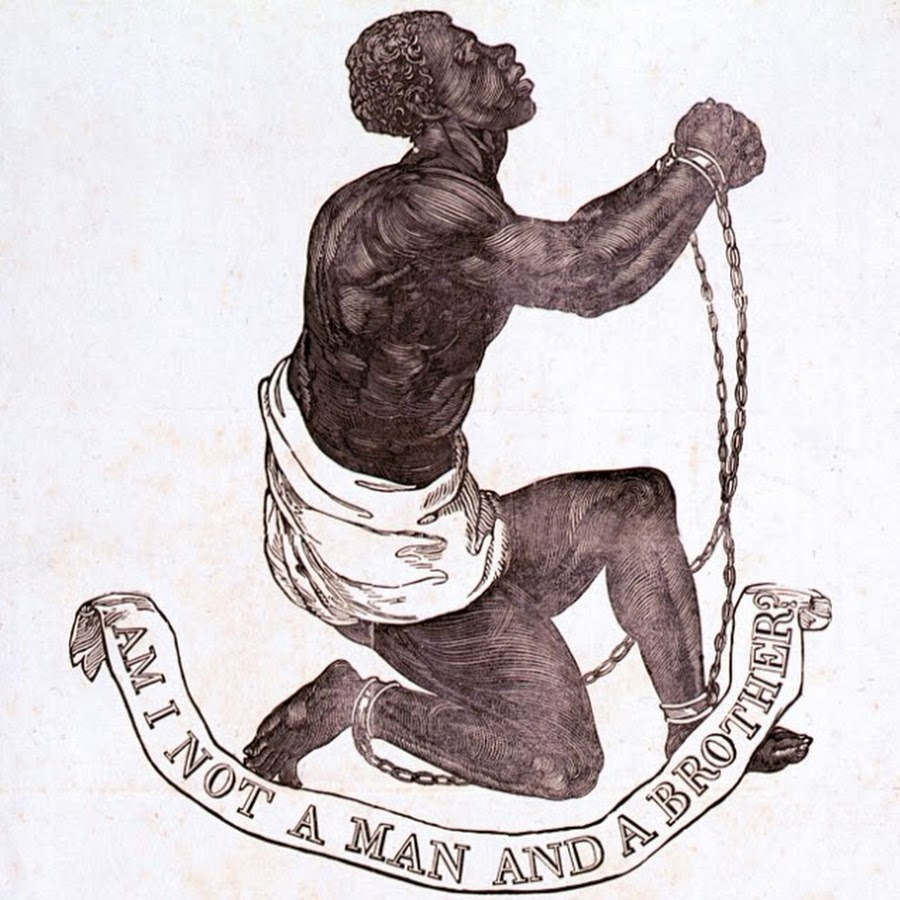

On this day, a unit of 80 former slaves was established by the then Administrator of the Lagos Colony, Lt. John Glover. This was during his trip back to Lagos from Jebba in Kwara State, where he had a shipwreck. Their crew became known as the Hausa Constabulary (a police force covering a particular area or city).

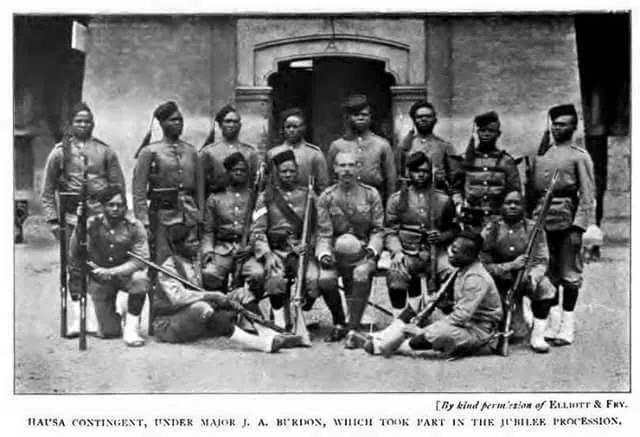

The Hausa Contingent, Under Major J.A. Burdon, Took Part in the Jubilee Procession [Elliott and Fry/Pinterest]

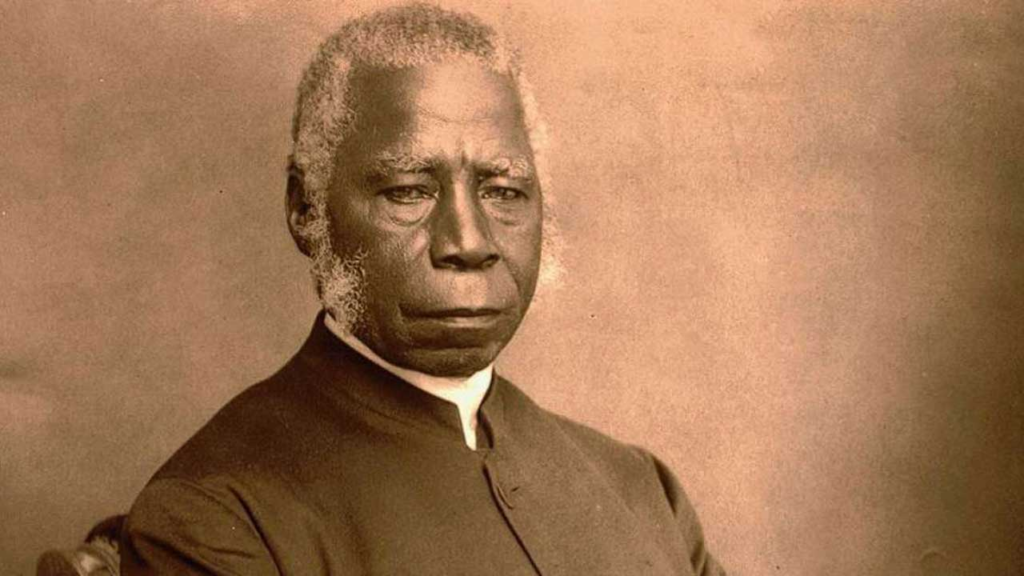

Sir John Hawley Glover (1829-1885) [Heritage. nf.ca]

A detachment of the Hausa constabulary was assigned for their first military operation in the Asante War of 1873-74 on the Gold Coast (Ghana).

The Gold Coast Constabulary of 1873 [Great War Forum]

This was because the Gold Coast once administered the Lagos colony. The detachment was deployed at Elmina and would later form the Gold Coast Constabulary in 1879, giving rise to the Ghana Army and Police.

As for the remainder of the Hausa Constabulary, they became recognised as the Lagos Constabulary in 1879 due to a formal ordinance by a new administrator, Sir Alfred Moloney.

Sir Alfred Moloney [Find A Grave]

But the Hausa and Lagos Constabularies would not be the only ones created.

There were other constabularies too

In 1886, following the 1885 proclamation of a British protectorate over the “Oil Rivers” of Eastern Nigeria, the Oil Rivers Irregulars (made up primarily of Igbos) came into existence.

During the same year, the Royal Niger Company Constabulary was created as the private militia for the Royal Niger Company (RNC) and became the Northern Nigeria Regiment. The Royal Niger Constabulary set up its Headquarters at Lokoja.

Hausa Soldiers, members of the Royal Niger Constabulary in 1895 [Asiri/Getty Images]

In 1891, the Oil Rivers Irregulars were rechristened the Niger Coast Constabulary (NCC) as a result of a change of province name from “Oil Rivers Protectorate” to “Niger Coast Protectorate.”

It was later regularised in 1893 under the command of British officers based at Calabar and formed the Southern Nigeria Regiment. It is here that we first know that the indigenes of the NCC force were made up of “one-third Yorubas and two-thirds Hausas”. The Yoruba component was a result of indigenes that were captured from previous wars in Yorubaland.

From 1893-1897, these constabularies would continue to exist separately until war made the British rethink their military strategies.

The Creation of the West African Frontier Force

France’s invasion of Ilo in the Borgu emirate in 1897 forced the British to make plans for military conflict, as they perceived the French invasion as a means of halting their trade relations.

Hence, the first battalion of the West African Field Force was created by Colonel Lugard on August 26, 1897. It expanded from a core of draftees drawn initially from the Royal Niger Company Constabulary. Two additional battalions, the 2nd and 3rd, were created in 1898.

Despite their preparations, there was no military conflict. However, there was already a demand for consolidating all British constabulary forces in West Africa from the War Office in London.

They argued that one central military force would lead to better coordination, an economy of force, and military efficiency in the scramble for West Africa.

This resulted in the establishment of a committee under Lord Selborne that formally separated Police (irregular) from Military (regular) functions.

It also consolidated all colonial forces—the Lagos Constabulary, the Gold Coast Constabulary, the Niger Coast Constabulary, the Royal Niger Company Constabulary, and the West African Field Force—into what became known as the West African Frontier Force under an Inspector General.

In January 1896, a “Lagos Police Force” was created, separated from the more military “Lagos (Hausa) Constabulary.” Subsequently, as part of the new Frontier Force arrangements, in 1901, the “Lagos (Hausa) Constabulary” formally became known as the Lagos Battalion, West African Frontier Force.

The remnants of the Niger Coast Constabulary and the Royal Niger Company Constabulary companies were merged to form the Calabar Battalion, West African Frontier Force.

The Split of the Northern and Southern Nigeria Regiments

In late 1899, the Niger Coast Constabulary, the 3rd Battalion West Africa Field Force, and the Royal Niger Company Constabulary were merged to form what became known in early 1900 as the Southern Nigeria Regiment, West African Frontier Force.

In May 1900, the consolidation of the 1st and 2nd battalions of the West African Field Force and Royal Niger Constabulary companies based in Northern Nigeria, led to the formation of the Northern Nigeria Regiment, West African Frontier Force, under Lugard.

The Gold Coast Regiment, West African Frontier Force, was not formed until August 1901. The Gambia Company, The Sierra Leone Battalion, and the West African Frontier Force were not formed until November 30, 1901. Therefore, the Southern and Northern Nigeria Regiments were senior to the others in order of precedence.

Colonial Era

The Origin of Present-Day Battalion Names

Due to the amalgamation of January 1914, the Southern Nigeria Regiment was merged with the Northern Nigeria Regiment to form one Nigeria Regiment, the West African Frontier Force.

Remembering the soldiers of the West African Force [Norwich Art Gallery]

From this point on, the various colonial battalions (initially comprised of eight companies each) took on new designations with specific numbers, which they have retained to this day, with minor modifications:

- The 1st Battalion of 1914 was the former 1st Bn. Northern Nigeria Regiment.

- The 2nd Battalion of 1914 was the former 2nd Bn. Northern Nigeria Regiment.

- The 3rd Battalion of 1914 was the former 3rd Bn. Northern Nigeria Regiment.

- The 4th Battalion of 1914 was the former 2nd Bn., Southern Nigeria Regiment (and thus the former Lagos Battalion, former Lagos Constabulary, former Hausa Constabulary, former Hausa Militia (or Guard) and original “Glover’s Hausas.”)

- The 5th Battalion of 1914 was the former 1st Battalion, Southern Nigeria Regiment.

Various re-designations have occurred since then. However, the 4th Battalion retained its number as part of The Nigeria Regiment.

The Legacy of the 4th Battalion

During World War 1, when the number of battalions was expanded to nine, it was known as the 4th Regiment, West African Frontier Force. This was attached to the King’s Lancaster Regiment.

In 1920, after the war, the number of battalions was reduced to four but then expanded to five, several years later. The West African Frontier Force became the Royal West African Frontier Force in 1928.

Headdress of the Royal West African Frontier Force [Military Sun Helmets]

Prior to World War II, the unit was known as the 4 Bn, Nigeria Regiment, Royal West African Frontier Force. During World War 2, it was known as the 4th Battalion Nigerian Rifles.

The last colours of the RWAFF used were reportedly presented in 1952 by Sir John Stuart Macpherson, GCMS, then the Governor General of Nigeria. The colours were retired in 1960, when Nigeria became independent, and remain preserved in the Battalion Officers’ Mess to this day.

The Nigeria Regiment became The Queen’s Own Nigeria Regiment, the Royal West African Frontier Force in 1956, the Royal Nigerian Army in 1960, and The Nigerian Army in 1963 (when Nigeria became a republic).

Independence Era

The Effects of the Nigerian Civil War on the Army

The Nigerian army’s troops rapidly expanded with the start of the Nigerian Civil War (or Biafra War) in 1967. Troops of 8,000 in five infantry battalions and supporting units rose to around 120,000 in three divisions by the end of the Nigerian Civil War in 1970.

Soldiers in the Nigerian Civil War [Peter Williams/Wikipedia]

This also led to an extreme shortage of commissioned officers for the right positions. Newly created lieutenant-colonels commanded brigades, and platoons and companies were commanded by sergeants and warrant officers. The effect of this was the 1967 Asaba Massacre, which led to the murder of 1,000 civilians of Igbo descent.

At the end of the war, the Nigerian Army was reorganised into four divisions, with each controlling territory running from North to South to deemphasise the former regional structure. Each division thus had access to the sea, thereby making triservice cooperation and logistical support easier.

The Impact

Later, sectors for the divisions took its place in place of the 1973 deployment formula.

The Nigerian Army, as of 2019, consists of 223,000 enlisted personnel. The Nigerian Army Council (NAC) oversees the army itself.

It is organised into combat arms, which are infantry and armoured. The combat support arms are artillery, engineers, signals, and intelligence. The Combat support services, which comprise the Nigerian Army Medical Corps, supply and transport, ordinance, and finance. Others include the military police, physical training, chaplains, public relations, and the Nigerian Army Band Corps.

The 1 Division is allocated to the North West sector with its headquarters in Kaduna. The 2 Division has HQ at Ibadan South West Sector, the 3 Division has HQ at Jos North East Sector; and the 82 Division has HQ at Enugu South East Sector.