If you’ve been religiously following the “Northern Nigeria Invasion” series, I have a bottle of wine to congratulate you. This is where we draw the curtain on it. However, key highlights from the two events we’ve covered are Lord Lugard’s British invasion of Northern Nigeria and the capture of the Bida and Yola Emirates.

Catch up:

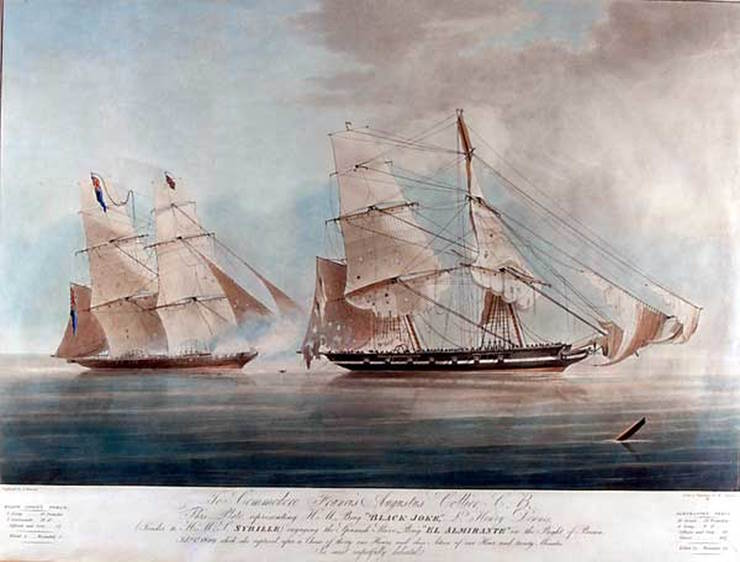

- The British Empire declared Northern Nigeria a protectorate in 1900 but had no territorial control. They needed to gain power over the region due to the fear of European rivals outsmarting them and to gain the local leaders’ respect.

- To do this, they called upon Frederick Dealtry Lugard, who grew from a British soldier to High Commissioner for Northern Nigeria in 1900.

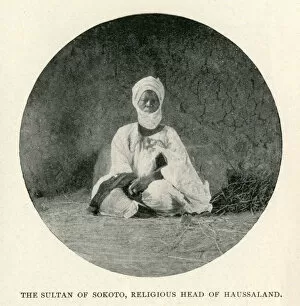

- After the official proclamation, he sent a memo to the Sarkin Muslmi, or King of the Sokoto Caliphate, to which there was no reply. This led to a rampage from Lugard to depose various emirates in the Caliphate.

- Amongst the lands he captured were the emirates of Bida and Yola. Bida fell due to a rebellion and their eventual alliance with the Royal Niger Company (RNC). Yola was captured due to the defiance of the Lamido, Zubaryu, who escaped capture from the British. The Lala tribe from Bornu State later killed him.

For today, take your straws to sip the last drink and dive deep into what ultimately ended the Sokoto Caliphate—the fall of the Kano and Sokoto emirates.

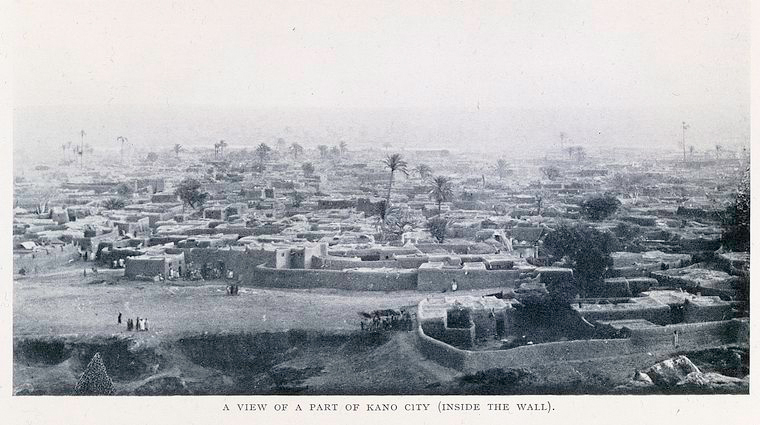

The Fall of Kano – January 1903

A view of a part of Kano City (Inside the Wall) [New York Public Library]

We must backtrack to Lugard’s feud with Sarkin Musulmi in 1900 to understand how Kano fell. His revenge mission against the launch started because the Sarki refused to respond to Britain’s proclamation of the North as a protectorate.

To better understand the feud, read: Northern Nigeria Invasion: How Lugard Disrupted Sokoto Caliphate

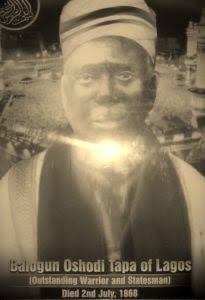

Lugard as colonial administrator, Northern Nigeria [Britannica]

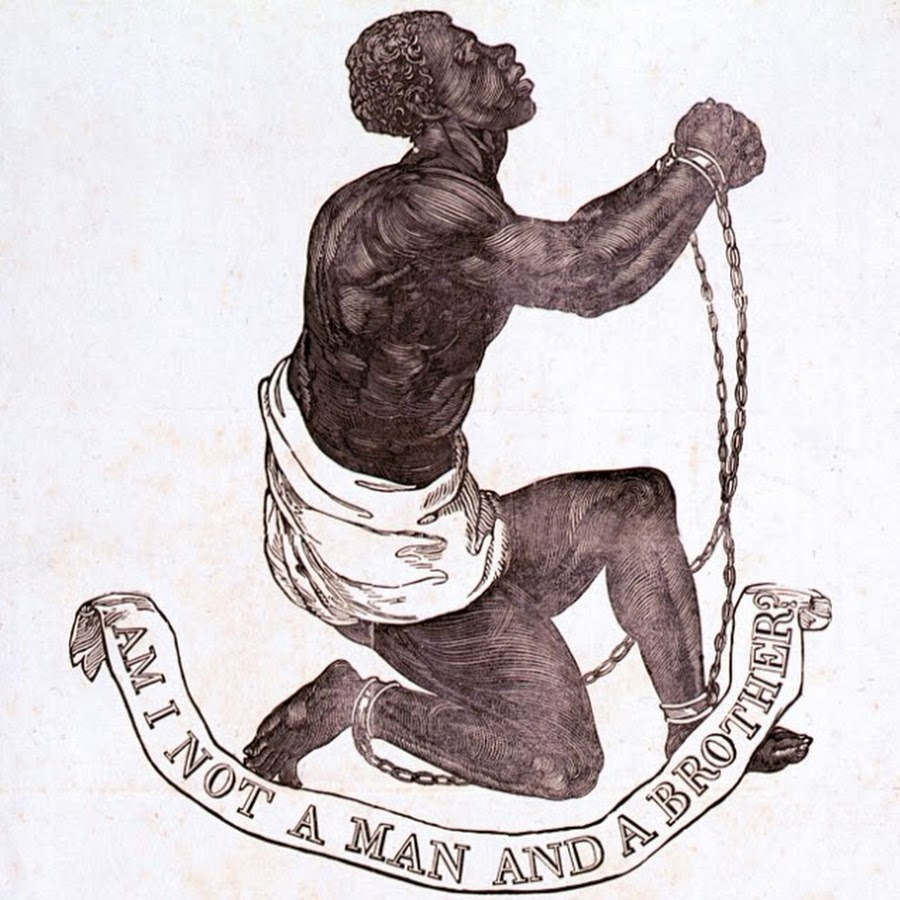

In 1902, Lugard finally received his long-awaited reply from the Sarki, but it wasn’t what he expected. Originally written in Arabic, the message says:

“From us to you. I do not consent that anyone from you should ever dwell with us. No agreement can ever be made with you. I will have nothing ever to do with you….This is with salutations.”

If we thought Lugard couldn’t get angry at Sarki, as we explored in the first edition, we might need to recount our words. The High Commissioner was as furious as ever, and as a result, he interpreted the Sarki’s response as an act of war, and an immediate annulment of the treaties between Sokoto and the Royal Niger Company (RNC) was drawn.

However, scholars believe the message was sent to Lugard’s second in command, Commissioner Wallace, instead of him.

How did Lugard launch the war?

You must know that for Lugard to start a war, he needed the support of Britain’s Colonial Office in London, and those folks were not ready to engage in more battles without a reasonable cause. Lugard, knowing this, eventually got his chance when a British resident at Keffi, Kano, Captain Moloney, was killed under “mysterious circumstances.”

And who better to blame for the murder than the warrior chief of Keffi, Dan Yamusa? It didn’t help that Yamusa was already openly defiant of Britain’s rule in the North.

The Sarki’s letter and Moloney’s murder were enough for Lugard to launch a war. And even though there was a window for negotiations with the new Sarkin Muhammadu Attahiru after the death of Abdurrahman, Lugard wasn’t having it.

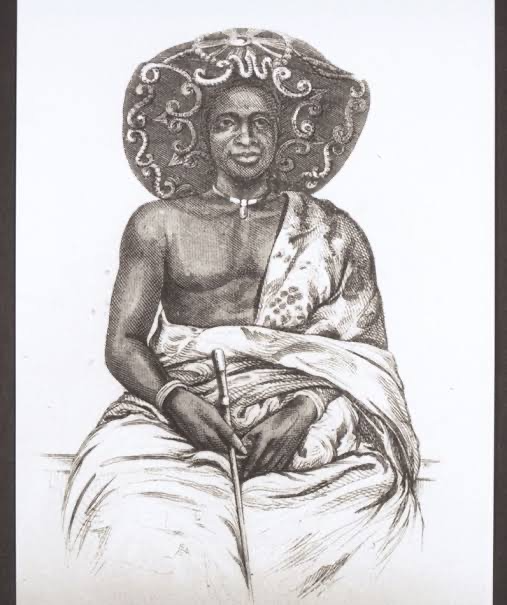

The Sultan of Sokoto, Religious Head of Hausaland [Getty Images]

He wanted to assert authority and was bent on using Kano to prove his point.

The Battle of Kano

To make his reasons for war convincing to the Colonial Office, Lugard claimed that the emir of Kano, Aliyu, was marching with warriors to attack the West African Frontier (WAF).

But in reality, the Emir was on the march—but only to pay homage to the new Sarki at Sokoto, hundreds of miles away. And even though the British didn’t buy Lugard’s excuse for a war, that wouldn’t deter him from his goal of total Northern Nigeria dominance.

However, Lugard still had a major problem—the walls of Kano. These walls were specially designed for defence, with a 40 feet thick base and 30 to 50 feet high. The city also had ditches and cultivated farmland inside its walls, which the people could use to feed themselves in cases of siege.

The Ancient Walls of Kano [Naija Biography]

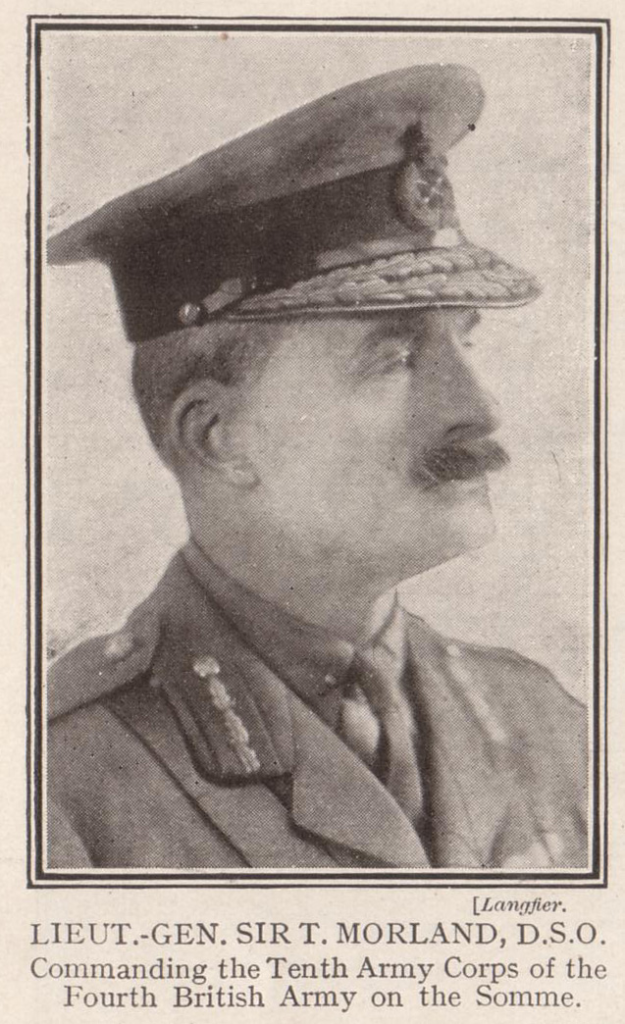

Surprisingly, Lugard’s captain, Colonel Morland, found little to no resistance from the Kano army due to the Emir’s absence. They blew a hole in the wall, stormed the city, stormed the Emir’s palace, and hoisted the Union Jack (the de facto national flag of the UK of Great Britain) on top of the city walls.

The Fall of Kano [Kano Chronicle/Twitter]

No British soldier was killed, and only 14 of them were wounded. Lugard then appointed the Emir’s younger brother as the new emir.

Up next on Lugard’s hit list was Sokoto

The Conquest of Sokoto Caliphate – March 1903

In February 1903, Colonel Morland wrote a letter to Sarkin Attahiru informing him of the fall of Kano and their anticipated attack on Sokoto.

“Sir Thomas Morland” [The Great War by Ed H.W. Wilson]

Attahiru replied by informing Morland that he would consult with his advisers and get back to him, but they could never conclude between negotiation, battle, or outward defeat. With their inaction, Morland’s army proceeded to march into Sokoto.

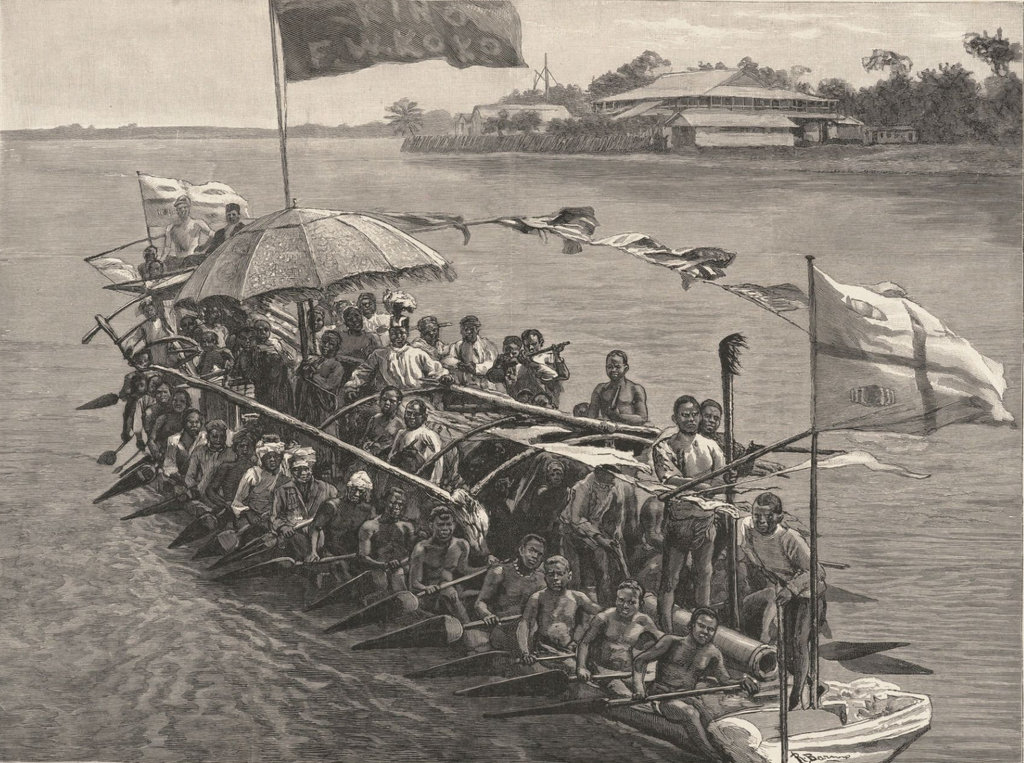

The War Against Sokoto Caliphate [LitCAF]

“We chase and kill until there are no living men”

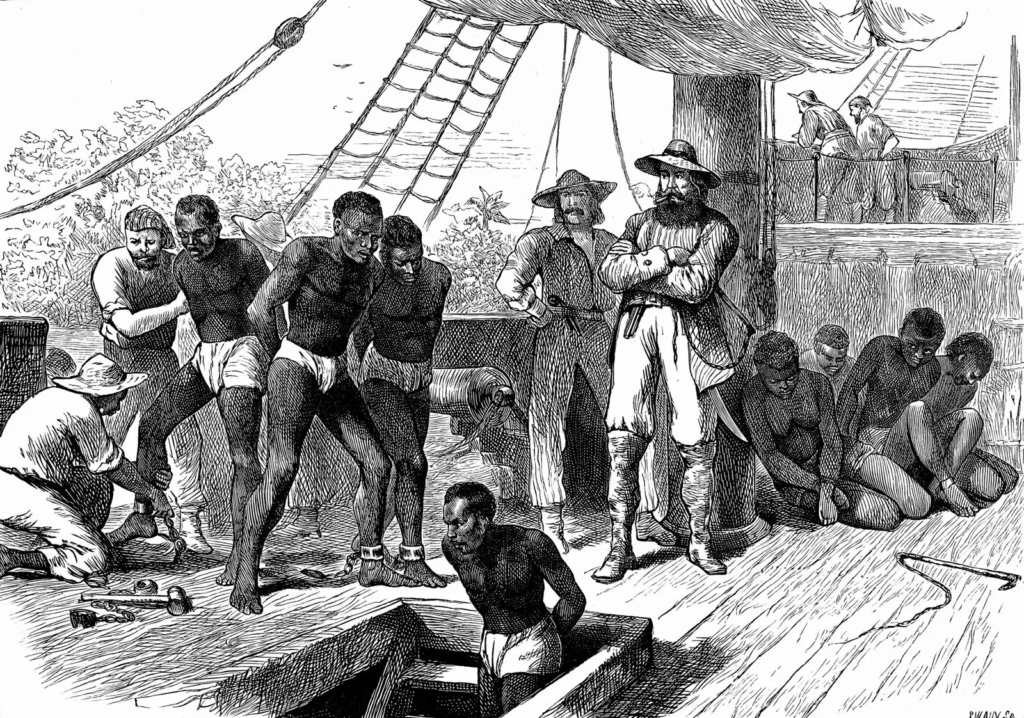

On March 14, 1903, Britain fought with the Sokoto Caliphate outside the city walls. Fighting without the safety of their walls was a grave mistake for the Sokoto army, as they were no match for the British artillery and machine guns.

However, the Sokoto army did not give up but stayed valiant until the end. They took the green flag of the Sarki into battle, and every time the flag bearer was shot, another would take his place—until all the flagbearers were dead. After the battle, the British infantry chased down what was left of the survivors and killed them. They also hacked legs and arms off corpses to take items of value. In a British soldier’s words:

“We chase and kill till the area is clear of living men — and we tire of blood and bullets.”

Comparatively, the casualties on the side of the British were remarkably small. Only two of their forces were killed—a carrier and a soldier.

The Aftermath

Sarkin Attahiru survived the battle and fled. Lugard asked Sokoto officials to nominate a new Sarki, and they eventually chose a ruler named Attahiru. In a March 21, 1903, proclamation, Lugard told the people that even though they could practise their religion, all independent Fulani rule had ended. The British system of government was here to stay.

What happened to Attahiru?

He was still on the run alongside Kano’s former Emir, Aliyu. While in exile, Attahiru was able to garner supporters from surrounding villages. This was due to the anger of the indigenes towards the British for deposing the head of their religion.

The British saw Attahiru’s fame and survival as a threat, and despite trying to capture the former Sarki six times at Burmi in the Borno Empire, all their efforts were in vain. In one of the battles, the British army got hit with poisoned arrows, which gravely injured two soldiers and six horses. To ease the two soldiers’ deaths, their colleagues shot them.

This article draws inspiration from Max Silloun’s “What Britain Did to Nigeria”