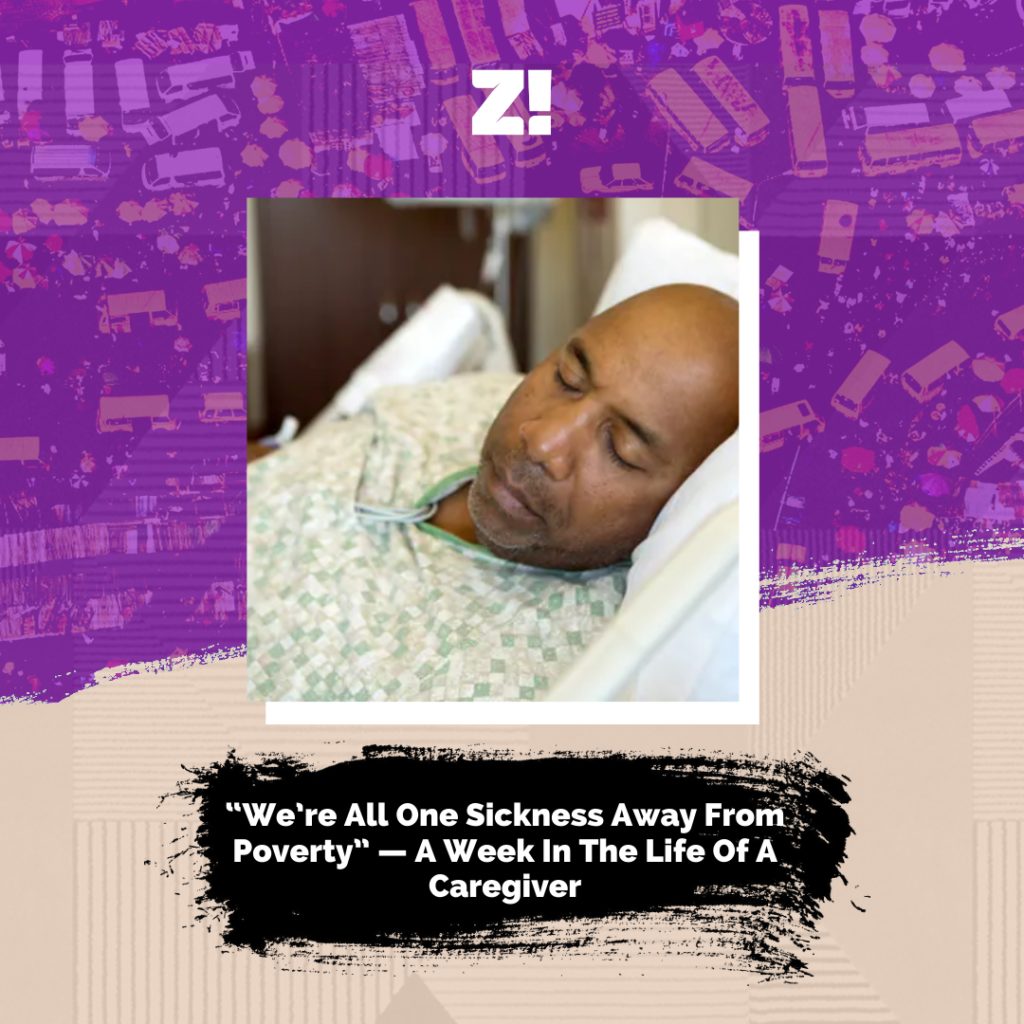

The subject of today’s What She Said is a 23-year-old Nigerian woman who is no stranger to the hospital. She talks about having breast lumps, dealing with heart attacks and an enlarged heart at 23, and enjoyment being her driving force.

Tell me something interesting.

I have had five heart attacks between 2020 and 2021.

Wait, how old are you again?

23. I’ll be 24 in December.

Let’s start from the beginning. Before the heart attacks.

Well, before the heart attacks was the inflamed appendix. When they found out, I was rushed into surgery. After the appendix was sorted, I was diagnosed with an ulcer three months later. I was 18 and in my second year of university. One thing I did notice was that after I graduated from university, the ulcer reduced to almost nothing. I guess stress had been a major factor.

That’s good, right?

Yeah, it is. Then towards the end of 2019, I started feeling pain in my right breast. When I went for a scan, it turned out I had breast lumps. I freaked out a bit because my mum is a breast/cervical cancer specialist nurse. I had grown up knowing how dangerous lumps are. On the 5th December 2019, I got surgery to remove the lumps.

How was surgery like?

The surgery went okay. It was done in the late morning and when I woke up by late evening, I was able to walk down the hospital stairs to my dad’s car.

The only abnormality was that during the scan they said I had two lumps, but during surgery, they removed four.

What was more stressful than the surgery, was post-surgery hospital visits. I spent most of my December going to the hospital to get my dressings cleaned. I even spent half of my birthday in the hospital. It was a very sobering day.

In between all of this, the lab results of the lumps came back and it turned out I had Benign Proliferative Breast Disease without Atypia.

What’s that?

It means I have a disease that causes cells to grow excessively and abnormally. While it is not cancerous, it slightly increases my chances of having breast cancer. It also causes me pain from the cells that are lumped together. Currently, I have two lumps in my breasts.

Wait, you have to regularly remove the lumps?

Well, yes, but I have decided not to. I just have regular breast exams now. If I keep removing the lumps, I may have no breasts left. I’ve gotten used to the lumps. Well, as used to it as the pain will allow.

Also, the last time I went to remove the lumps, the doctor narrowly missed slicing off of my nipple. I don’t even know how he did that, but I have blanked that part out of my mind.

Do you know I just clocked you haven’t even started talking about your heart attacks?

I have too many health issues, that’s why. With the ulcer and breast lumps, there’s still potential PCOS to deal with and ovarian cysts.

I am so sorry. That’s a lot

Well, my main issue now is my heart. It seems to be after my life. I have had a total of five heart attacks between 2020 and 2021. Two major ones, and three minor ones.

The first major one happened in May 2020. Before that, I had been having severe chest pain since February 2020. I brushed it off as ulcer pains, stress, or my body healing from the surgery. This was because the pain was in the middle and right side of my chest. The chest pain kept increasing. It got to a point where I could barely exercise and was tired all the time.

Then May 1st, 2020, I was cooking when my dad called me to his room. As I entered, I felt a pain radiating from my chest down my right arm. I fell, but luckily my dad caught me and started massaging my heart. I laid on my parents’ bed till the doctor came.

After that heart attack, I went to see a doctor. He gave me medication for the ulcer, and I really wanted to shout at him that what was wrong with me was more than an ulcer, but I didn’t. I faithfully took my medication. Then on the 28th of May, heart attack number two happened.

This one happened in my room and if not for my brother entering just as I fell on the floor, I may have been telling a different story now. After that, my mother carried my health on her head.

Wait, why was that doctor treating you for just an ulcer?

A lot of doctors kept saying I was too young to have any heart problems. Throughout all my hospital visits, I had to be asking questions and pushing them to do tests. The doctor just looked at my age and cancelled any thought of anything heart-related. Also, it’s probably because the pain is on my right side, rather than the left as it usually is.

When a doctor finally diagnosed me with ischemic heart disease, my first thought was “so no more alcohol for me again? I’m finished.” The doctor gave me three different drugs and sent me home.

Then I had to deal with comments from outsiders about my size. It took all my willpower to not punch people that asked stupid questions. My life was in the balance and people were asking me why I was so small. To top it off, I was put on a restrictive diet.

This sounds like so much, I am so sorry. How did you cope?

I was barely coping. I threw myself into work (I’m a writer/editor), read, and my tribe of friends really helped to ground me but it was still hell.

I was in so much pain, and there was physical and mental exhaustion. I was managing well then on the 24th of June, heart attack number three happened.

This heart attack led to the diagnosis that truly tipped me over the edge. They told me that the right side of my heart is enlarged. The doctor tried to play it off as nothing too serious, but I knew it was bad. I was having shortness of breath, cold hands and feet and chest pain.

I got home after this diagnosis and cried. I was down for a whole week, and then I entered a self-destructive spiral. I was eating and drinking anyhow and was skipping my medication.

What grounds you now?

At first, nothing grounded me. From 2018 to the middle of 2020, I was just floating through life. It’s only from lockdown, I was forced to finally confront my mortality and my life and my baggage. I became more honest with myself and I realized I had to get back as much of my sanity as possible. I stopped self-destructing so much and started taking my medication again. I also found out I have an incredible tribe of friends. I started journaling and doing stretches.

I guess you can say I am currently grounded in the knowledge that everything is useless and when you break life down, the core of its meaning is nothing and that’s okay. I am here for a good time and not a long time. Just because my body seems to hate being alive, doesn’t mean I have to let it make me miserable all the time. I am seizing my joy by fire by force. Enjoyment is my driving force.

Overall best in enjoyment.

That’s me. It’s just that it gets lonely being chronically ill. I can’t get into a serious relationship because I don’t want to bother anyone with my health issues. I also won’t have sex because I’m afraid I might pass out. It has been two years without sex now. Being chronically ill is a very lonely place to be, but I’m currently at the most emotionally healthiest I’ve been all my life.

I’m lucky I have a supportive family. Both my parents have tried for me. My uncles and aunts too. Although they get on my nerves sometimes, like when they complain about what I eat when they see me snacking. I eat healthy 90% of the time. They should allow me to have my guilty pleasures. I have lost my mind too many times to be policed by people like this.

I know they mean well, but they should allow me. I am in pain every day of my life. The least I can do is enjoy what I can.

For more stories like this, check out our #WhatSheSaid and for more women like content, click here

[donation]