Since we started the Citizen History flagship, we have journeyed together through the significant conflicts of pre-colonial Nigeria.

We’ve visited the Ekumeku War, the ‘Expedition’ of Benin, the Bombardment of Lagos, and the Northern Nigeria Invasion. We’ve shown how our ancestors fought valiantly but yet lost to Britain.

Today’s story takes us back to 1906, when Lord Lugard, the High Commissioner of the Northern Nigeria provinces, considered locals instead of British soldiers for leadership of the newly colonised lands.

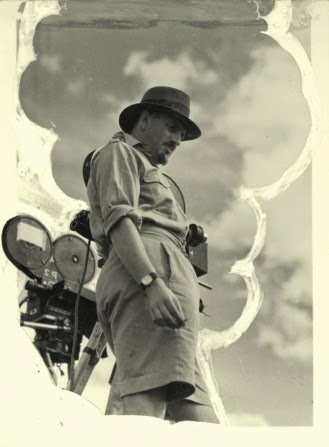

Frederick Lugard, 1st Baron [Wikipedia]

Why did a British representative trust the locals to rule over other locals, and how did he execute that?

This era in Nigeria’s colonial history is known as Indirect Rule.

In June 1934, this picture was taken of the governor of northern Nigeria, Lord Lugard, and other country rulers at a zoo in London. [Getty Images]

Indirect rule is a system of administration in the colonies where local leaders—although front-facing with the people and ruling with native politics—dance to the British tune and follow all orders the administration gave.

But why was there an indirect rule?

There were several reasons:

- Britain didn’t have enough personnel for Nigeria’s enormous land mass. By 1925, there was approximately only one administrator for every 100,000 Nigerians. Even Lugard admitted it once by saying, “Nor do we have the means at present to administer so vast a country.”

- Even if they could, there was an issue with Nigeria’s high mortality rate. Between 1895–1900, up to 7.9-10% of British officers died yearly. British officers were reluctant to move to Nigeria, and those that did wanted a higher salary, which Britain couldn’t give.

- According to some reports, the colonial masters also wanted to limit uprisings from the Nigerians, who would rather be ruled by one of their own than a foreigner.

Now that you understand why indirect rule happened, let’s walk you through what life looked like in both Northern and Southern Nigeria under this rule:

Indirect Rule in Northern Nigeria: The Day in the Life of An Emir

Emir of Kano in 1911 [Wikipedia]

In northern Nigeria, the Emir was the traditional and spiritual leader of the emirate. Using Islamic dictates, he had a judicial system with alkalis, a revenue generation system, and several titled officials. The British did not see the need to overhaul their systems but took control of them instead.

The Emir in colonial Northern Nigeria was not elected by the people but rather selected by the colonial government, which informed the kingmakers of their preferred candidate. So, even though he is ruling the Northern people, his allegiance goes to the British Crown, and this is backed up with letters of appointment and oaths.

During his tenure, an Emir knows that his most important duty is tax collection, not for himself but on behalf of the British. Delayed tax payments could lead to their removal.

The budget for running the British colonial administration also came from these taxes, which were 25% of total taxes collected. The Emir never ruled alone but always had a “resident” with him as Britain’s colonial administrator for “advice”.

The Emirs’ lives of indirect rule started properly in 1900 and ran till the 1940s.

Indirect Rule in Southern Nigeria

South Eastern Nigeria

Implementing indirect rule in the North was a piece of cake for the British due to their existing political systems. But in the East, applying this method was hell.

This was because the ethnic groups (Igbo, Ibibio, Efik, Ekoi, Ogoni, and others) did not believe in the existence of one ruler but rather lived in autonomous communities. To solve this problem, the British devised a solution in the form of “warrant chiefs”.

A Day in the Life of A Warrant Chief

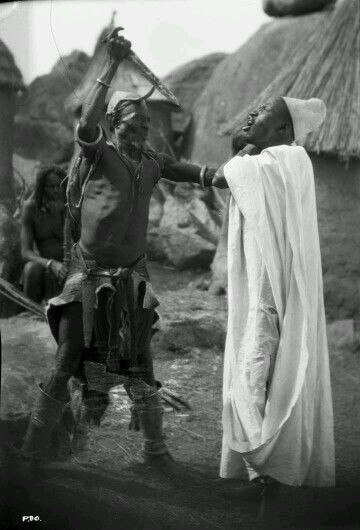

An old kind of warrant chief, from The Nigeria Handbook, 1936 [Ukpuru]

A warrant chief knows he is being called one due to the certificate the British give him. He is not a ruler but a representative of the colonial government.

Despite his power, he is more notorious than popular in the community, as the indigenes see him as disrupting the status quo and betraying them. Due to this resentment, his interactions with the villagers would always be laced with curses and abuse.

The colonial administration made warrant chiefs tax collectors, used them to conscript youths as unwilling labourers for the colony, and oversee judicial matters.

The warrant chief knows he was not selected through any process, so he doesn’t need to be credible or reliable to the people to get the job done. He would be fraudulent with taxes being paid and would invent new ways of extorting the people of their funds.

The actions of the warrant chiefs met such great resistance that he would experience revolts, including the Aba Women’s Revolt of 1929.

South Western Nigeria

The first meeting of the Yoruba Obas in Oyo, 1937 [Asiri Magazine]

Indirect rule was neither perfect nor unfit for the South West. The region had traditional rulers, often known as the Oba, who were held accountable under a democratic system with several checks and balances. The Oba, who already received taxes and tributaries, worked well for the colonial administration for tax collection.

But this did not go without revolts and protests across different towns. One of them is the Abeokuta Women’s Revolt, which led to the removal of a King.

The Impact of Indirect Rule in Nigeria

Here are some of the effects of indirect rule on modern-day Nigeria:

- It led to the rise of nationalism across Nigeria

- The title of “warrant chief” has gradually turned into a hereditary title today in the South East, with the descendants claiming to be from “royalty”. Key figures in Nigerian politics today are descendants of warrant chiefs, e.g. Senate President Godswill Akpabio is the descendant of warrant chief Udo Okuku Akpabio in Ikot Ekpene, former minister of foreign affairs, Geoffrey Onyeama, is the grandson of warrant chief Onyeama of Eke, etc.

The story elements of this episode of Citizen History were sourced from “What Britain Did to Nigeria” by Max Silloun.